Memories of a 31 Mike: An Interview with Vietnam Veteran Powhatan Red-Cloud Owen

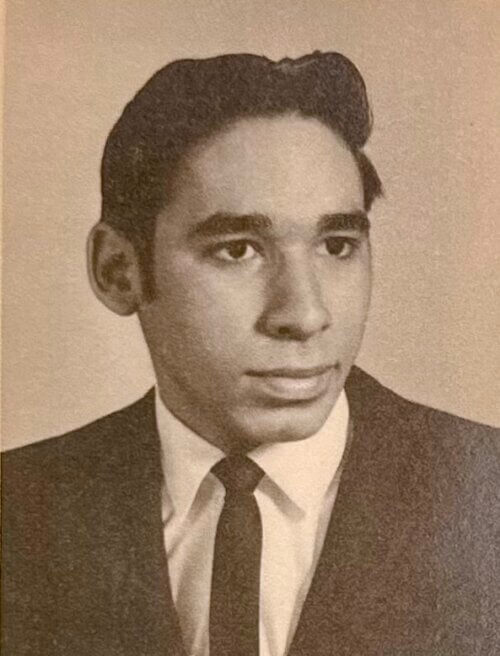

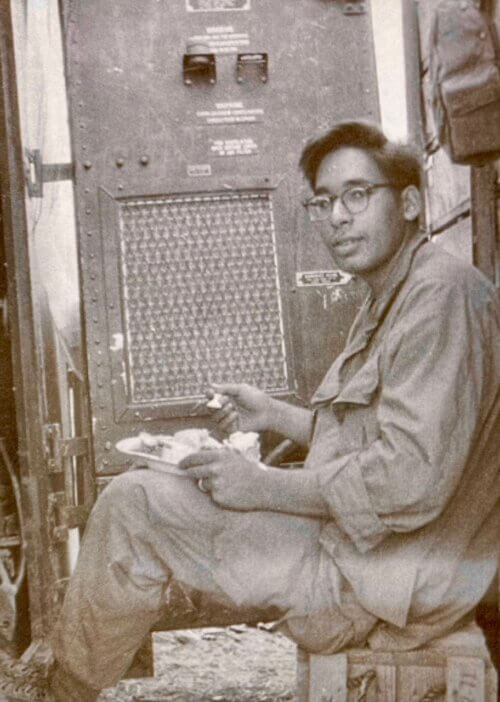

Powhatan Red-Cloud Owen just before he left for Vietnam 1968.

Powhatan Red-Cloud Owen, 1968

Davis Jansen is the Virginia War Memorial’s Education Intern for the summer of 2025. A rising senior at Virginia Commonwealth University and a history major, Davis is working on a new blog series that features interns interviewing veterans about their war time experiences.

On Tuesday, July 22, 2025, I sat down with Powhatan Red-Cloud Owen, a Native American Vietnam War Veteran and volunteer at the Virginia War Memorial (VWM). In this interview, Powhatan talks about his upbringing, service during the Vietnam War, life and career after, and his religious and spiritual beliefs that have guided him through his experiences. Owen, a Native American of the Chickahominy people from Charles City, Virginia, went overseas to Vietnam in the fall of 1968, arguably the height of the war’s action, where he served as a radio man in the Army’s 23rd Americal Division. After sustaining injuries from the enemy in action, he served the rest of his time as a member of the U.S. Army Honor Guard for funerals based out of Ft. Lewis, Washington. After his time in the Army, he worked as an appliance technician for Sears until he retired in 2005. For decades, he did not speak about his experiences in Vietnam. Owen began to open up around 2010 when he formed a close bond with the VWM among other veterans’ organizations. Like many Vietnam Veterans, he was given no welcome home after his return, however through the healing process of time, along with his faith, he found his home here at the VWM.

You grew up in upstate New York as a Mohawk Indian, what was it like moving to Virginia and being accepted into the Chickahominy people?

“I actually grew up in Long Island and Queens, not upstate. My mother was from Virginia and the Chickahominy people, so I had already visited them during her homecoming events.”

“Being accepted wasn’t difficult as my mother was already part of the Chickahominy people. All Native Americans feel a sense of connection regardless of tribe, so I only ever felt accepted and loved.”

What was your experience facing racial discrimination at home as opposed to overseas in Vietnam?

“There were many racist people at the time. I remember when I was about eight or nine years old, we were in New Kent, Virginia, and my father and I were denied service in a restaurant for being Native American. It was the first time I experienced racism. At that young age, I couldn’t even articulate what had happened. However, in Vietnam, I received no discrimination.”

Graduating Class U.S. Army Southeastern Signal School

What were racial relations like between white and minority enlisted soldiers?

“In a hot LZ (Landing Zone), you’re not going to find a racist or even an atheist. Everyone is either calling for their mom or God. When you’re in the heat of battle, you don’t worry about what someone’s background is or what race or religion they are.”

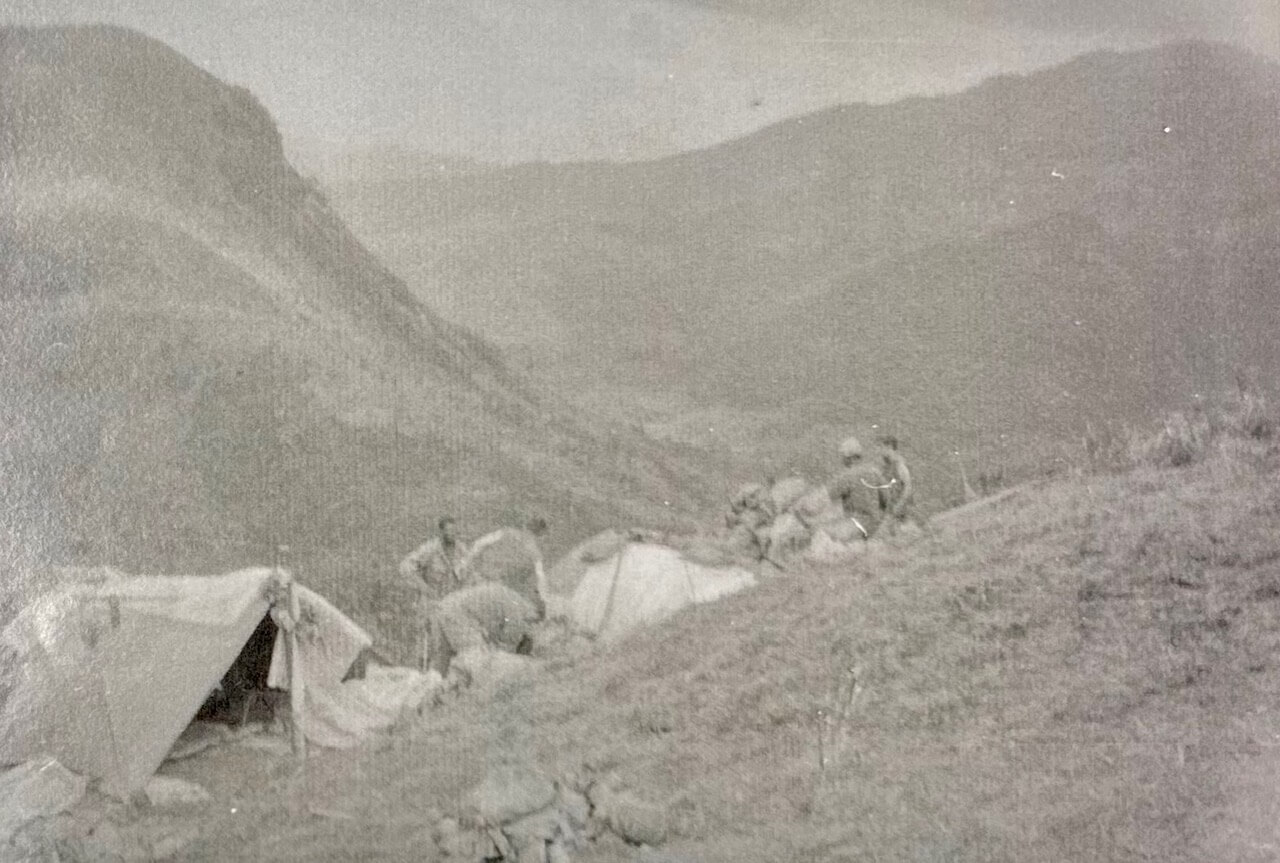

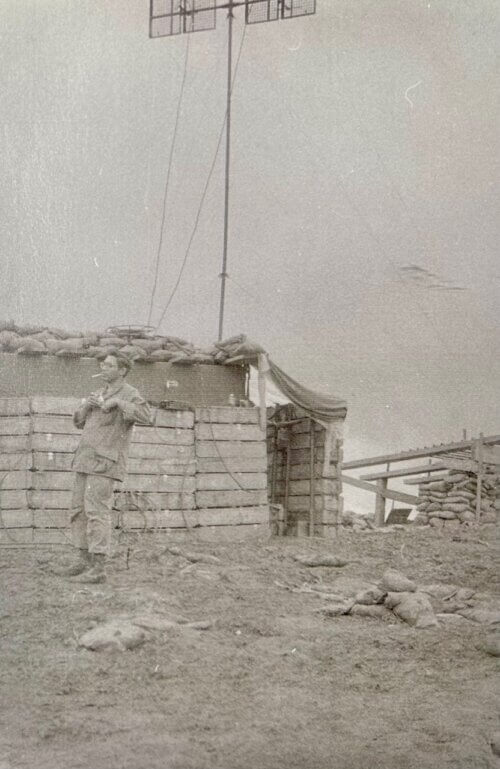

Landing Zone (LZ) in Vietnam, 1968

What were your day-to-day operations while in Vietnam? What was your role?

“I was a radio man who set up communications at LZ’s. I was in the 11th Infantry of the 23rd Americal Division. 31 Mike was my MOS.” (Military Occupational Specialty)

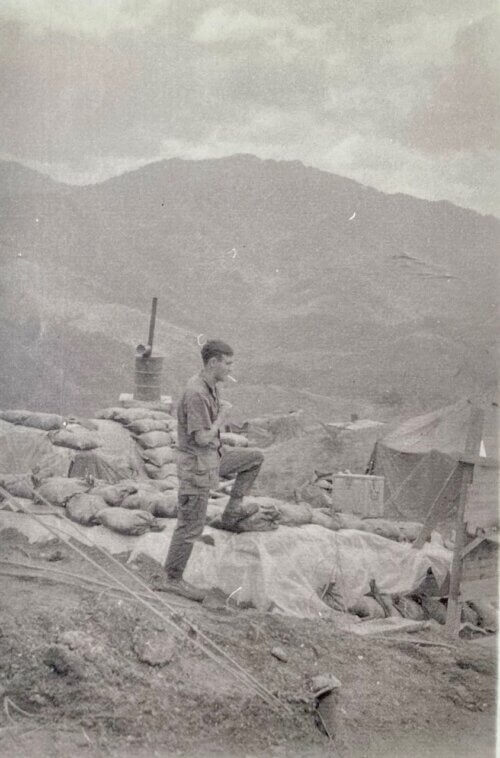

“We were based out of Chu Lai and would fly in with five- or six-man teams. We had to put up these large waffle shaped antennas to bounce communications from LZ to LZ. We would be dropped down on the side of a mountain and look out for Charlie [the enemy] below us.”

(In the Vietnam War, the Viet Cong were nicknamed “Charlie.” This stemmed from the radio phonetic alphabet: “V” for Victor and “C” for Charlie, thus “Victor Charlie” – shortened. Thus it became slang for the Viet Cong, the enemy or southern supporters of the northern enemy.)

“We had to be quick in setting up these large antennas, and we would protect the Mickey 6 (communication hut) with sandbags to stop mortar fire.”

“You had to be good with your longitudes and latitudes when calling fire on enemy positions otherwise you would fire on your friendly soldiers. When we heard the enemy below us, we would call in their positions so we could glass [view with binoculars] it.”

While in Vietnam, what was your understanding of the U.S. Army’s main goal or mission?

“I didn’t have a clue.”

Owen in Vietnam, 1968.

What was your reaction to the mass number of anti-war protests and anti-war sentiments during the Vietnam War.

“Protesting against the government is something my people have been doing for 500 years so I understood that.”

“However, I am proud of what I did and who I served with, I earned my medals and ribbons, and no one can take that away from me.”

Did anti-war narratives translate to the soldiers? Helmet graffiti, drug usage, overall low morale, etc.

“I only saw pot smoking. We used to trade cartons of cigarettes with the Vietnamese. They would return cigarettes with marijuana stuffed inside, and in return we would give them a carton of cigarettes.”

“People that wrote on their helmets had been there a while, so I never did that.”

Owen, communication antenna in background.

Owen in the mountains of Vietnam 1968.

42,000 Native Americans participated in the Vietnam War, do you think they are highlighted properly in history?

“They are highlighted in the sense that Native Americans were rewarded with medals and decorations like any soldier. However, most books about Native American Vietnam servicemen were either written by themselves, or someone close to them.”

“I recommend any educators or students to read Strong Hearts, Wounded Souls by Tom Holm. This is a great book about Native Americans in Vietnam with multiple interviews of veterans. He also has a book on Native American code talkers in World War II, titled, Code Talkers and Warriors. Tom Holm is from the Cherokee people and served in Vietnam as a Marine.”

“I also recommended Warriors in Uniform by Herman J. Viola, who is not a Native American himself but does an excellent job covering our experiences.”

We often hear that Vietnam Veterans received no welcome home after the war, what was your personal experience?

“This was definitely the case, there was no welcome home, or parades, aside from seeing your family, I didn’t take any personal offense to it.”

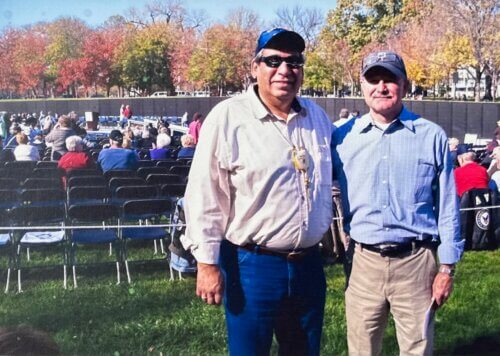

“The years after the war were difficult to adjust to, and for a long time, I didn’t want to speak about my experiences. Really, the Virginia War Memorial is my welcome home.”

How has prayer and religion helped change your perception of your time in Vietnam?

“I was brought up by my mom who was a Baptist, but I never paid much thought to it when I was younger. Since about 1990, I have embraced the Baptist faith along with spiritual beliefs from my people.”

“People wonder how I can be a Baptist and have native American traditional beliefs at the same time. I tell them that it is like a train going down two rails at once that will ultimately lead me to the same place and time on the same train. One religion is not better than the other.”

“Attending cleansing and healing ceremonies in the years after the war helped me come to terms with and accept my experiences.”

Tell us about your favorite memories in Vietnam, the friends you made, the good experiences you had, seeing new places, etc.

“I had to laugh a little bit at your questioning, because I didn’t have a good memory in Vietnam. My favorite memory was the day I left that place.”

“I did make good friendships in Vietnam; my best friend was named Kip.”

Owen with his best friend Kip, after the war in 2012.

What do you hope future generations learn from the Vietnam War and the veterans who experienced it?

“I hope and pray that future generations will learn to love one another.”

“War solves nothing, brings misery, and most of the victims are women and children.”

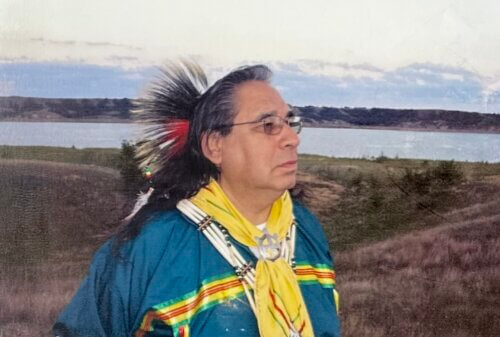

Owen in his straight dance regalia.

Towards the end of the interview Owen told me one last story about meeting a young Vietnamese woman at a folklife festival in 2005. Owen was wearing a turtle medallion made by his mother, the tribal symbol of his people. When the young Vietnamese woman admired the medallion and remarked how the turtle was also sacred in her culture, Owen felt called to give the turtle to the woman. He noted how any trauma or negative feelings he felt towards his time in Vietnam were lifted from him that day.

Owen has been inducted into three warrior societies and notes that the most important aspect of joining these societies were the healing ceremonies. To truly heal, Owen had to fully open up to his tribal Elders and share all his experiences. As mentioned in the interview, this was a crucial process to bring Owen peace and relief from his trauma.

Davis Jansen with Powhatan Red-Cloud Owen, 2025

Thank you, Powhatan, for taking the time to talk with me about your experience. And thank you for your service.

All photography used in this blog post is © Powhatan Red-Cloud Owen, all rights reserved.