Nursing on the Homefront: An Interview with Lieutenant Colonel Constance Collins-Davis, U.S. Army Nurse Corps

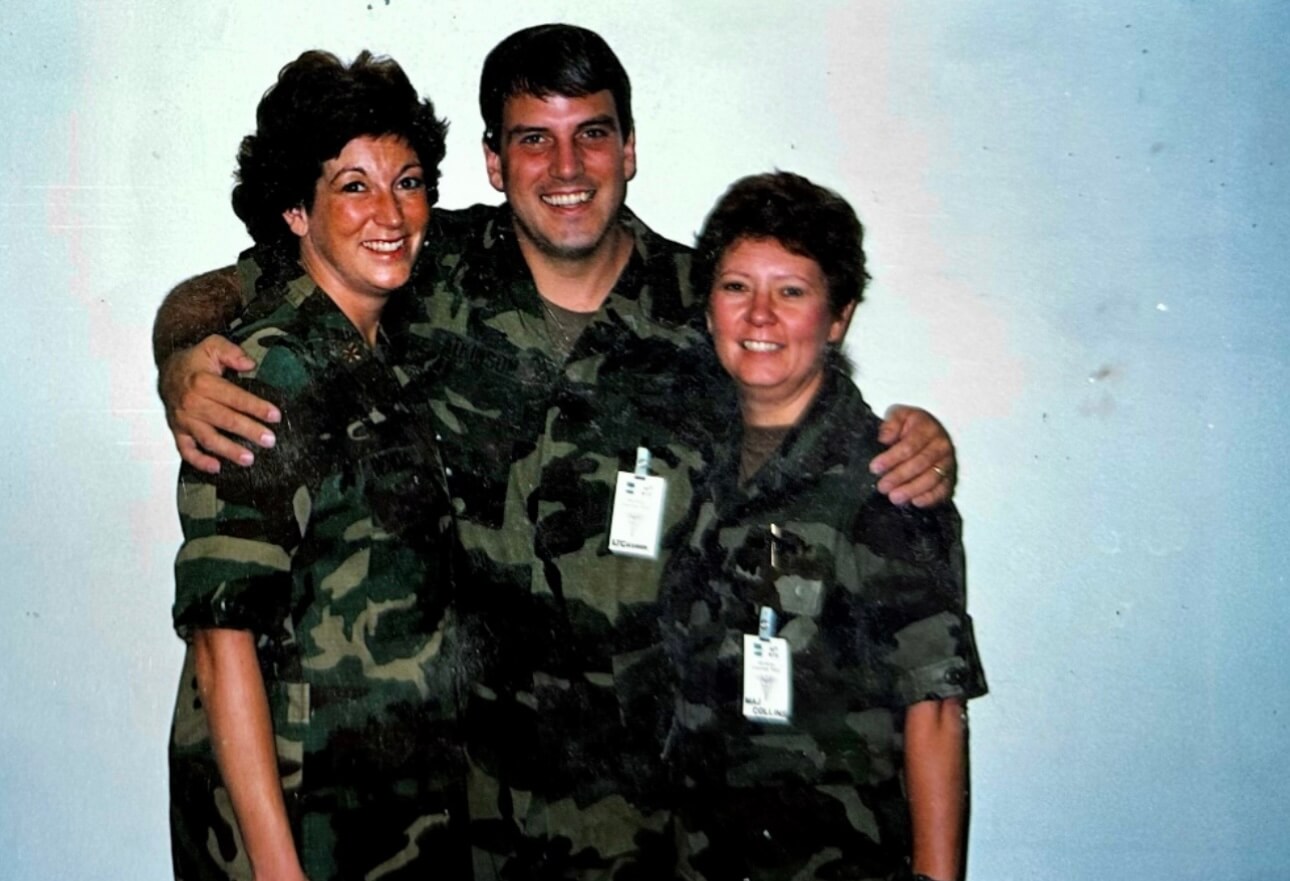

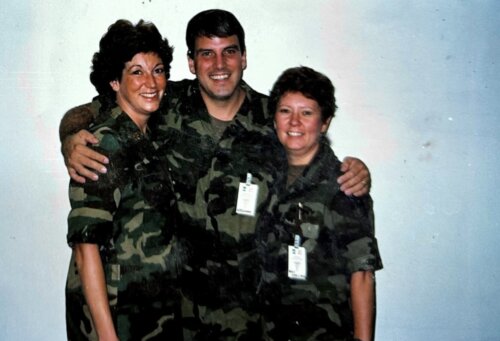

LTC Collins-Davis (right) pictured with fellow Army nurses, Robin Benchart (left) and Sid Atkinson, M.D. (middle) in 1986 at the 339th Hospital in Richmond, Virginia.

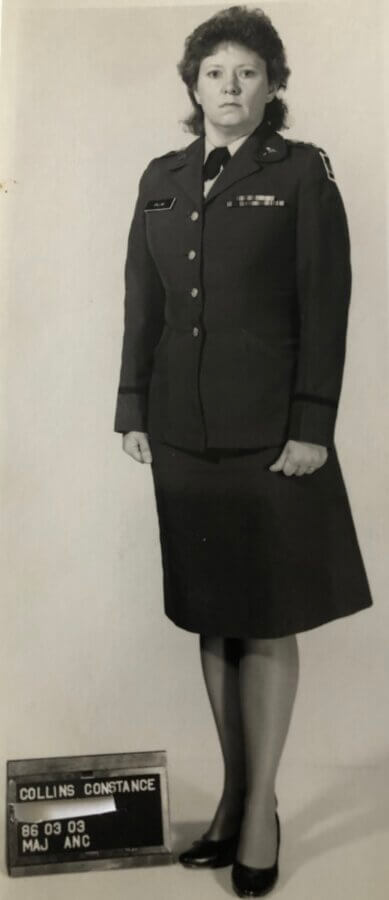

LTC Collins-Davis pictured in uniform.

Cynthia Lin is the Virginia War Memorial’s Education Intern for the fall of 2025. A senior at Virginia Commonwealth University and a dual major in History and Urban and Regional Studies, Cynthia is working on a blog series that features interns interviewing veterans about their service in the U.S. Military.

In the 1970s, the American Nursing Corps was evolving. That decade was marked by the first woman in United States history to obtain a general officer rank and was appointed to the position of the 13th U.S. Chief of the Army Nurse Corps (ANC) and Brigadier General. This era ushered in new reforms for women, allowing for a paralleled promotion structure to men in the Army. In this session, Lieutenant Colonel Constance Collins-Davis joins us to share her story as a nurse in the United States Army and Army Reserve from the early 1970s to the late 2010s.

LTC Collins-Davis lives near Cold Harbor, Virginia, and regularly volunteers at the Virginia War Memorial. She began her military career at Fort Sam Houston in San Antionio, Texas for basic training. Once completed, her first assignment was at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, where she went on to serve from Fort Drum to Fort Jackson along the East Coast. In 1990, she was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and has since worked at the Veterans Affairs Hospital and St. Mary’s Hospital in Richmond, Virginia. LTC Collins-Davis is active in her local community and has led multiple medical and mission trips to Haiti from 2005 to 2015. At the age of 69, LTC Collins-Davis retired from the Army Reserve in 2019 after nearly 50 years in service. On September 30, 2025, LTC Collins-Davis sat down with us to discuss in detail her career in the military, spanning from her early education in the military, the challenges she overcame, and reflections on her service.

Q: Tell us about your background growing up. Why did you want to be a nurse, and how did you get involved with the U.S. military?

A: I knew I wanted to be a nurse since I was six years old, but I wasn’t sure what to do after I finished nursing school. I had family who served in the Revolutionary War, and my father served during World War II—he received both a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart. So, when in my final year a recruitment officer visited the school, I talked to him. He came to my home and went over with me the benefits of the military, like getting to see the world and traveling. My father wanted to know if I was sure this was what I wanted to do, but I knew I wanted to experience military medicine myself. Later, I didn’t know that I would be a nurse anesthetist until I was in the [operating] room and knew that this was where I was supposed to be.

Editor’s Note: LTC Collins-Davis enrolled in anesthesia training courses at the University of Pittsburgh.

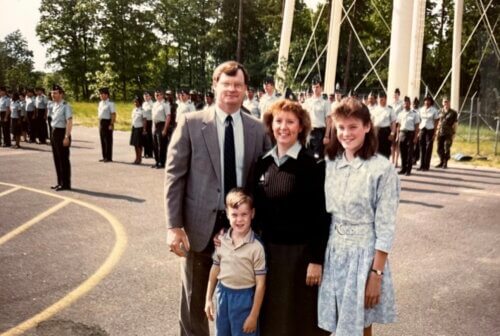

LTC Collins-Davis with family after being promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in 1990.

Q: What was your role as a nurse in the military? What did the education in the Army look like for nurses?

A: I worked all along the East Coast—from Fort Drum to Fort Jackson. It was not necessary, but I also ran ambulance and helicopter calls, which were a lot of fun. When I was in the 80th Division, I conducted ARTEPs (Army Training and Evaluation Programs) throughout those hospitals. We were training people on how to treat war wounds. That was where I learned how to do moulages [realistic wounds for educational training] on patients. The Command Sergeant taught me how to do those, and he later became one of my friends. It was different because most of the people we were training were already healthcare workers and familiar with the practices [of medicine]. The main thing for them was the battlefield simulations that you had to treat patients under. I found that it was easier to teach people when you enjoyed what you were doing and laughed with those around you.

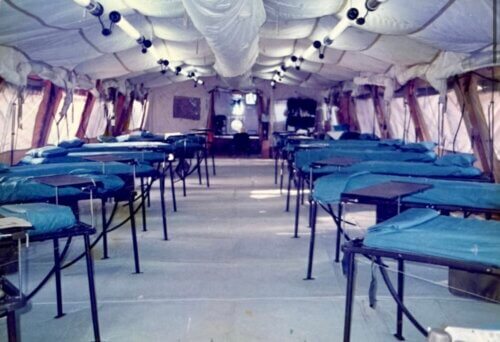

An army field hospital tent used for training simulations.

Q: What specific training did you have to undergo as a nurse?

A: I remember that at that point, medical personnel were required to take the Combat Casualty Care course, which required a great deal of mental and physical commitment. One time, we were training in the woods and had to rappel down a 30-foot wall. They [those with active combat experience] went hard on the nurses and doctors. After clipping myself in, I went down about halfway when I lost my footing. I was suspended there upside down, and the Sergeant told me I had [gotten] myself there and I had to get myself out. I was able to get myself down after swinging around, but that [experience] really stayed with me.

Q: Where did your career take you after joining the Army Reserve? How was your experience there?

A: After being stationed at Aberdeen, I enlisted in the Army Reserve and moved to the VA [Veterans Affairs] Hospital and then St. Mary’s [Hospital]. While at St. Mary’s, I worked a fragmented schedule, but without built-in time for my military duties. I was working 60-hour work weeks and raising four children, so I often had to use my own vacation time to balance everything out. I feel like I am more appreciated now than I was during the war.

LTC Collins-Davis (right) pictured with fellow Army nurses, Robin Benchart (left) and Sid Atkinson, M.D. (middle) in 1986 at the 339th Hospital in Richmond, Virginia.

Q: Were there any challenges that you faced during your time in the ANC?

A: I was on active duty during the 1970s and entered the military during the Vietnam War. All of us were required to wear our uniforms at all times, even during transport. While walking in the airport for a transfer from Fort Sam to Aberdeen Proving Ground (APG), I had food thrown at me by protestors. The culture is completely different now than it was then. Later, I wanted to explore the city and somehow got caught up in an anti-war demonstration. All I could think [was] what would my supervisors think. I was still very green at the time and didn’t know much about the city.

[Interviewee pauses]A: There was also a weight issue at that time. I saw a lot of good people not enlisted due to their weight [Editor’s Note: At this time, LTC Collins-Davis was stationed in the 339th General Hospital]. If someone did not make the standards, they would be taped around their arms and waist for a BMI test. It was all based on whatever your height and weight was. Now, they are much more lenient about people’s measurements when considering them for enlistment.

LTC Collins-Davis in uniform, 1986.

Q: What was it like being a woman in the Army? Did you face any difficulties during your service?

A: I worked with a lot of good, dedicated people in the hospital. I only had friction with surgeons, but I would stand my ground. Most of the time they would back down and give me respect because otherwise I could have just left, and they didn’t want that. In 1993, I moved down to the 80th Division and experienced some discrimination as a woman—even in the 1990s. At that time, I was a lieutenant colonel working with a doctor who ranked as a major [Editor’s Note: The rank of lieutenant colonel presided over that of the rank of major in the Army]. I was shocked when the visiting general came to the hospital and spoke to the major before he approached me, despite outranking him as a lieutenant colonel. I was one of the few women in the building, and I was an older woman as well. I felt like I was being observed under a microscope.

Q: How did your medical trips to Haiti shape your career and outlook in life?

A: I led ten medical trips to Haiti from 2005 to 2015 with my mission organization. These trips provided basic medical treatment and drug administration to locals. I was on the ground six weeks after the 2010 Haiti earthquake. Our building had a big crack in the foundation, so we were set up on the veranda behind a church. We would see all kinds of people looking for care, and we would try to help them, although it was mostly placing and removing stitches for them. Doctors Without Borders heard about us and came to visit, so I gave them a tour around the area. After a few years I couldn’t return because of the tensions within the country, but I enjoyed working with the people. I have since retired from the Board of Haiti Outreach Ministries but wish that I could return to Haiti sometime.

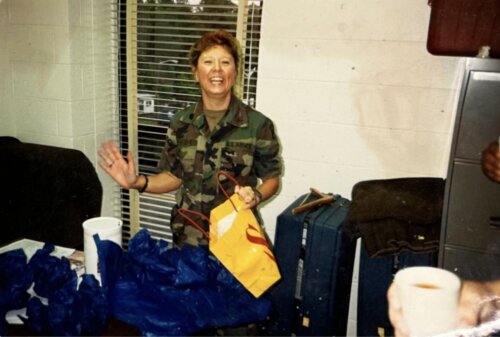

LTC Collins-Davis unpacking medical supplies.

Q: Do you have any advice for America’s current youth?

A: I really loved being a nurse. There is a 31,000 personnel shortage of nurses in Virginia, so I try to encourage others to pursue nursing. During my trips to Haiti, I was able to encourage five volunteers to go to nursing school, and I even wrote a girl a letter of recommendation. You really have to be their cheerleader. I highly recommend going into the military, as they are very pro-education and support careers throughout all branches of the military. I even received the equivalent of a Nurse Anesthetist’s PhD, and a Military Science Master’s, while working as a nurse. The option was available to me, so I took the opportunity when it came. [Editor’s Note: LTC Collins-Davis enrolled in these courses before these programs were officially implemented and titled.]

Display for LTC Collins-Davis and other female veterans, at the Virginia War Memorial

Thank you, LTC Collins-Davis, for joining us at the Virginia War Memorial to speak about your journey and for your service in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps.

LTC Constance Collins-Davis with intern Cynthia Lin at the Virginia War Memorial, 2025.

All photography used in this blog post is property of © LTC Constance Collins-Davis, all rights reserved.